so, happily, it can continue to enhance the experience of that piece on permanent display, long after the rest of the show has closed. But while Seurat worked so creatively at discovering what he could fit in, 30 years later, Matisse seemed to be working very hard to find what he could take out. Recent x-radiographs have uncovered seven stages in that painting's eight years of development, and two computer stations allow viewers to scroll through diagrams of each one. Even better, since each stage can be seen completely, the exhibit has all 4 versions of his monumental sculptural relief, that begins with something like a woman's back, and ends with something more like an arrangement of cylinders. All of which may be fascinating , but does the piece get any more radical - or just more peaceful and decorative? And is this process of abstraction,"the modern method of construction", with all its layering and scraping, really the "radical innovation" which the title of this exhibit would suggest?

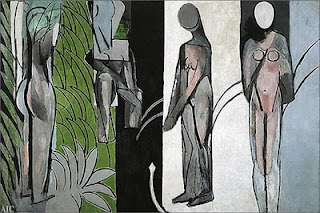

All such techniques can also be found in Cezanne's "Three Bathers" (also in this exhibit) , which was done 30 years earlier and later owned by Matisse himself.

Reducing the human figure to a kind of hieroglyph, Cezanne pioneered a kind of painting that was more like a personal calligraphy and less like a window on the world.

So Matisse’s innovation was just the development of his own personal logographics. His earlier work in this show, the “Blue Nude” of 1908, resembles the brash, angry, explosive modernism of Picasso and Stravinsky.

But then his painting became more subdued, as he cocooned himself into a quiet, prosperous domestic life, probably in response to the war that was decimating his countrymen.

Contemporary art theory requires that important artists be radically innovative, and if the results feel angry , dreary, or otherwise unpleasant, so much the better, as they trumpet the arrival of a new, modern world and challenge the self satisfied, mindless hedonism of the bourgeoisie.

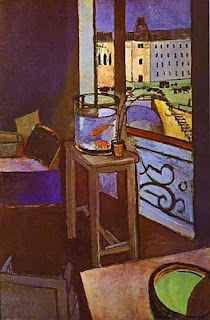

It’s just that Matisse doesn’t always fit that mold, and hard as he may have worked to expunge anecdotal details, he still liked to paint flowers, goldfish, and pretty girls, and their charming ambience comes through, especially in his small, dry point or monotype figure drawings and various views of Tangier or his studio in Quai Saint-Michel.

Rather than exemplifying the radical, iconoclastic, transgressive innovation demanded of a modern European artist, Matisse’s work from 1913-1917 seems to better exemplify an aesthetic that is traditionally Asian.

Still Life with Goldfish, 1914

Still Life with Goldfish, 1914Some different responses are here:

Erik Wenzel

Janina Ciezadlo

No comments:

Post a Comment