Monday, December 26, 2022

Suchitra Mattai "Osmosis" at Kavi Gupta

Saturday, December 24, 2022

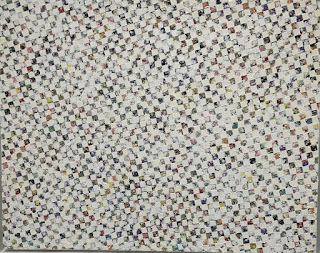

James Little - Black Stars and White Paintings

James Little - Black Stars and White Paintings

Kavi Gupta Gallery

************

Spangled Star, 2022, 72"x72"

A Review of James Little - Black Stars and White Paintings at Kavi Gupta

*********

Down in Memphis, the patterns of colored stripes in his first museum show of the year was typical of his work. They’re as emotion free as a page torn from a book of color theory. There isn’t even a sense of wonder, balance, or humor. Just the pure, unfiltered energy of a technical investigation.

But when his monumental “Black Stars” are shown beside his perforated “White Paintings”, the game changes. The black stars exemplify the drive and singularity of purpose that’s still required for blacks to rise above the dark legacy of oppression. The rows of regularly spaced tiny windows into his white paintings reveal an apparently limitless variety of colorful, sensual miniatures - like the urban grid of a trendy white neighborhood where every high rent condo shelters someone’s unique opportunity for self gratification. The artist acknowledges this racial binary in this exhibit, but also tells us “That whole racial aspect isn’t any more important to me than trying to paint some emblematic arrangements with two tones of black.” - so this may be the last time he crosses over into racial stereotypes - even though it would not hurt his career. These same black and white paintings were probably what got him into the Whitney Biennial this year - his first appearance ever.

Monday, December 19, 2022

The Language of Beauty in African Art — Art Institute of Chicago

And then one might ask: just how were these pieces selected? Obviously 19th century Africans could not be given the job — but what about African artists and collectors from our time? Wouldn’t their sensibilities of life and Art likely be closer to that of their great grandparents? There are a few who are even carrying on their traditions.

Friday, November 11, 2022

Tcharam ! ... at The Very Serious Gallery

“Tcharam!” … an upbeat Portuguese fanfare equivalent to “ta-da!’ in English …. is indeed appropriate here as it announces the first time that students of Odd Nerdrum have exhibited together in Chicago. The work of the Norwegian master himself does not appear - and his mythopoetic Baroque paintings are way too Euro-old-school to be shown in any local art museum. (though some small pieces have occasionally made it into Art Expo) You can go online, however, to get some idea of his imagery as well as philosophy of art. He is an outspoken proponent of what he calls “kitsch”

Collecting figurative tchotchkes has been de rigueur among Chicago Imagists from Roger Brown to Phyllis Bramson -- but Nerdrum’s favorite kitsch can only be found in art museums - not gift or toy shops. It’s appropriate for an elite, sophisticated, historically minded viewer who seeks catharsis rather than the comfort or thrills of popular entertainment. It cultivates sincerity rather than irony and aims for an emotional maturity rather than the perpetual adolescence so celebrated in Chicago. “Its nature is deeply antagonistic towards the present” and it “lavishly relishes imitation”.

In one way, Nerdrum’s pedagogy is also old-school. His students don’t pay but they do have to model or assist in studio production. Contrary to traditional ateliers, however, he doesn’t teach students how to paint like himself - he encourages them to develop their own vision- whatever it may be - and the three former students in this exhibit have indeed gone in three different directions. What they share is an emphasis on narrative content at the expense of more formal qualities. These two concerns need not be conflicted -- as proven by many art museum masterpieces - but if an immediate emotional impact is all that an artist wants -- that’s likely all a viewer will ever get. If that's what the Nerdrum school calls “kitsch” - that’s fine with me -- but not when they offer the paintings of Rembrandt, Turner, Caravaggio, Vermeer, and Chardin as examples.

Trevor Knapp’s pieces appear the most effective at delivering an immediate feeling with clarity - and their grating anxiety would work well to illustrate a gothic novel. Bruno Passos seems to deliver puzzlement rather than any other emotion. Something dramatic may be happening - or maybe these pieces are more about the history of painting. “The Sculpture Thief” has me thinking about early Picasso while “Black Coat” references Giacometti - though they are not quite as strong.

Most puzzling are the dream like fantasies of Adam Holzrichter. He has created a a luminous, casual, rumpled world without straight lines or volumes, buzzing with a kind of post-coital energy. His series, of dissipated floral altars belongs on the stage of Tannhauser’s Venusberg. A similar ambivalence toward sexual desire appears in “Lady Komodo” - an anti-erotic variation on Velazquez’ Venus - here reclining in her boudoir beside a pig and a few of the planet’s largest living reptiles. The subject is outrageous - yet the blurry painting summons a yawn rather than any feeling of anger, disgust, contempt , or even humor.

According to Tomas Kulka, the oft quoted author of “Kitsch and Art” (1994); “The objects or themes depicted by kitsch are instantly and effortlessly identifiable” Other than Trevor Knapp’s, most of the works in this show would not qualify as such. Yet neither do many of them have the distinctive formal tension of art. These are, however, highly motivated young artists who don’t follow trends. There’s no telling what they'll be doing in a decade or two.

Monday, November 7, 2022

Ian Mwesiga at Mariane Ibrahim : Theatre of Dreams

It felt like Summer when I visited this show last Saturday, but the temperature dropped at least ten degrees when I entered the gallery. Blues, greens, and grays dominated the walls - challenged only slightly by a few tepid pinks. Each oil painting presented a flat, wooden, solitary figure engaged in a highly competitive activity. All of the young men were basketball players. In their crisp, new jerseys , they were all good enough to make the team. Several of them were especially athletic. Michael Jordan himself could never soar that high in the air. But they were not competing on a basketball court - they were silhouetted against a barren landscape whose colors are noted above. Most of the young women were at a grand piano - but none were touching the keys. They sat beside, slept against, or danced as a ballerina upon it. Actually - I don’t think any of these young Ugandans have ever practiced, much less mastered, either of these activities. They just fantasize about it - presumably to escape a reality that offered so little stimulation, either mental or sensual. I can’t recall healthy young flesh depicted so un -erotically — except perhaps in Byzantine icons. Possibly the artist grew up in a rather severe form of Christianity. The only young women not next to a piano were near picked apples in a garden -- one of which is posted “CAUTION ; BEWARE OF SNAKES”.

Traditional python worship is still common among the Bunyoro of western Uganda, but the snake-garden-apple trope obviously came from another civilization - as did the clothing and architecture that are depicted. As a consequence of European colonialism, these young people are foreigners in their own country. Every step must be taken with care.

The young artist’s website shows his earliest works, and in 2017 the subject matter was quite different. Mwesiga’s “School of Dance and Beauty’’ was an obvious homage to Kerry Marshall’s “ School of Beauty, School of Culture” - again demonstrating the international appeal of our local super-star. People joyfully participating in a social setting has been pictorialized in many times and places. But it’s unusual to find young people depicted as lost at the threshold of adult life. One good artist who comes to mind is Tetsuya Ushida (1973-2005) - who likely stepped in front of a speeding train at the age of 32. Mwesiga, however, may not share the unhappiness of those he is depicting. He’s probably just painting what he sees around him - and it's quite an achievement to portray it so beautifully, compassionately, and without an upfront political agenda.

He shows his subjects as dreamers, not victims. As he sees more kinds of things, he will probably move on. This is a career that I would like to follow.

Tuesday, November 1, 2022

Arvie Smith at Monique Meloche

As Arvie Smith says in an interview “ Even though I’m a professional, when I’m out on the street I’m seen just like a pimp- I’m treated just like any other black figure which in some instances have just about as much rights as a horse, a dog, or a chair.”

Apparently he has been sufficiently outraged by race-based humiliation that he devoted the past two decades of his life to expressing that through art. ( and maybe even earlier - the pieces in this show date only from 2006 to 2022. The artist was born in 1938)

Smith also suggests that he would like his work to initiate a dialogue - but what can be discussed with a man who is yelling? It would be futile to mention the cost and the consequences of the Civil War or Civil Rights legislation - or even the successes of his own career. He wants viewers to feel his pain - though curiously his cartoonish mages are as breezy and ebullient as Disney cartoons. His work feels screwball joyful until you recognize the symbols and the narrative of hate and degradation. He appears to be enjoying himself even as he expresses the misery of racism.

The image of young boys looking at their reflections in “Echo and Narcissus” (2022) is the most poignant. They’ve been taught to see themselves as empty-headed goofs or monsters. Does the artist still feel that way about himself ? Some viewers may feel empathy for the damage done to innocent children - others may regret that the artist had not yet taken responsibility for a self image that only he can repair. Both are correct - and so this body of work contributes to the polarization that defines this moment in American life - providing career opportunities for extremists of every persuasion.

Will this work hold interest when that moment has passed ? These are more like agitprop storyboards than the painterly work of Robert Colescott who introduced Smith to the genre. The figure drawing is suitable for political cartoons, but does not rise to the level of the snappy characterizations of that 18th Century icon of sarcasm, Thomas Rowlandson. And there is nothing like the formal power of a recent master like Charles White.

But the manic, bubbly, high pitched energy of his surfaces do echo those of his mentor, the ABX painter Grace Hartigan. Plus, the artist seems desperate to cram as many tropes into each work as possible. More is more. Subtlety - tossed out the window - lies spreadeagled on the pavement below. If he lived in Chicago, Smith might be called an Imagist. Recently he has begun to explore Classical mythology. It’s quite a stretch to conflate Leda and the Swan or the triumph of Bacchus with racism in America. It gives some hope that he may ultimately present a life not tethered to victimhood. And maybe he already has - - - if you just ignore the subject matter.

Wednesday, October 26, 2022

Mitch Clark at Oliva Gallery

Monday, October 10, 2022

DePaul Museum, Wrightwood 659, Art Institute of Chicago - What’s new

Three museums seen on a Saturday afternoon in October

**************************

DePaul Museum

A Natural Turn: María Berrío, Joiri Minaya, Rosana Paulino, and Kelly Sinnapah Mary

Within A Natural Turn, Berrío, Minaya, Paulino, and Sinnapah question Western and Eurocentric standards of beauty, femininity, and womanhood by reimagining the surreal—creating imaginary journeys around the metamorphoses of the body and redefining what it means to be human. For these artists, surreal imagery is useful in that it can at once call attention to the conflicted legacies of imperialism and colonialism, challenge the status quo, and subvert one’s experience of reality. Surrealism within this exhibition is a means to interrogate structures of power. (Gallery signage)

The above boilerplate of social justice art theory conveniently ignores the "structure of power" that produced this exhibition itself : a major local university with a 36 acre campus in an upscale Chicago neighborhood and a billion dollar endowment. Whatever status quos may be getting challenged here, the authority of educational institutions and their social political agendas are not among them.

Not that I need artists to express angst, alienation, or despair —- far from it —- but the self righteousness of the educated elite is no more uplifting - primarily because it’s boring. No spiritual struggle is evident here. It relies on the cleverness and political correctness of ideas to establish value. The pieces in this exhibit are pleasant and well made, but they have no more formal power than childrens’ book illustrations. As Kerry Marshall has demonstrated, identity art doesn’t need to be this way.

But still - I do have a favorite; Kelly Sinnapah Mary. As she tells her story in gallery text, she was born on Guadeloupe and did not know, until adulthood, that her ancestors came from India rather than Africa. So now she’s producing delightful small figurines with black skin and three eyes. (In Hindu spirituality, the third eye chakra plays a major role)

WRIGHTWOOD 659

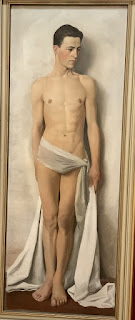

The First Homosexuals: Global Depictions of a New Identity, 1869-1930

Art Institute of Chicago

Bridget Riley

Man in Garden, 1952-55

David Hockney

The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020

Thursday, August 11, 2022

Nick Cave : Retrospective at the MCA Chicago

Nick Cave is best known for his “Soundsuit” series, begun over thirty years ago. and now numbering over 500. With all its raukus, oversized, colorful variations, it is truly exuberant. More importantly for the artist’s standing in the contemporary artworld, it initiated a connection between his career and racial politics. Explanatory text tells us that the first Soundsuit was a gathering of sticks intended to conceal the artist’s racial and gender identity in response to the then recent beating of Rodney King. Within the racial justice wing of the contemporary artworld, that reaction is understandable since both King and Cave were young African American men in 1991. Outside that mindset, however, we might note that King could only find work as a part time laborer while Cave already had an MFA, a career in fashion, and a teaching position at a leading art school. King caught the attention of law enforcement because he was speeding, not because he was black. Then he led police on a high speed chase to avoid an alcohol test and possible suspension of his parole. Initially, all the officers involved were acquitted of using excessive force. In a second trial, two were convicted, but even then the presiding judge acknowledged that most of the beating was necessary to subdue the suspect. King’s status as a victim of racial injustice was questionable, but Cave presented it as clear cut. As he play-victimized himself, he simplified, personalized, and polarized a complex situation. As polarization in American politics has grown exponentially over the following decades, threatening the republic itself, we now might ask whether the artist really was acting responsibly even though he proclaimed himself “an artist with civic responsibility”

None of which can diminish the joyful visuality of these pieces, especially the wackiness and wonder of “Speak Louder” (2011) the most choreographed Soundsuit installation on display. Paradoxically, if any political message were intended it would appear to be cautionary. The seven sequin-suited humanoids are eyeless, earless, faceless, walking megaphones - presumably broadcasting “truth” at high volume. An appropriate metaphor for agit-prop art of all persuasions. One might also note that this piece is owned by two museums, the Chicago MCA and the Buffalo AKG. It doesn’t need to be on permanent display as the masterpieces of ABX painting often are. The intensity of an artist’s personal touch is not the issue. As with most of Cave’s work, fabrication was done by others. There’s a thrill in the surprise of first viewing - but beyond that, what’s left to see? Contrast that with Sam Gilliam’s “Cartouche” (1981), a painting now hanging on the museum’s lower level in memorial to his recent passing. One can never see enough of a good painting.

Accompanying “Speak Louder’ is one of Cave’s circular fabric tondo’s hung high up on the wall. It’s a colorful foil to the monochrome sound suits below - but it’s more decorative than expressive. His spectacular tondo’s shown at the Cultural Center in 2006 felt so much closer to an artist’s eye, hand, and spirit.

The rest of the exhibition is mostly in a darker tone. Cave delivers a message of racial grievance with his enshrinements of racist memorabilia. As quoted elsewhere, he’s been “on a crusade to find the most inflammatory, oppressive, despairing objects that I could find around the country.” And again, one might ask - is this really behaving responsibly? Even the museum of racist memorabilia in Michigan doesn’t show pieces this repulsive. Would Cave claim that these represent the majority opinion in any white community? Or is it only evidence of a fringe that may never go away ? As others presumably share his feelings of oppression and despair, what is supposed to be the positive outcome?

In many other pieces, Cave makes statements about black identity using bronze body casts taken from his own body parts. The artist happens to have a buff, heathy body - but body cast shapes express no inner spirit as carved or modeled figure sculpture can do. They retreat from surrounding space rather than seize and organize it. The resulting mood is grim, regardless of how uplifting the intended ideas may be. In contrast, Cave also uses plenty of mass produced, low end sculpture throughout the exhibit - kitschy toys, lawn decorations, and gift shop collectibles. The mood they create is often giddy because that’s what sells, and as we know, every true Chicago artist since Roger Brown is supposed to collect it. The one mood that Cave’s work does not engender is that of deep contemplation. It’s more like political cartoon.

The cloud of metallic spinners that fills the airspace of the atrium introduces this Nick Cave retrospective as if it were a kind of carnival. There is a sensory overload of flashing light and color. Like the rest of the exhibition, it includes both store-bought and bespoken artifacts. Many are fanciful eyecatchers, but a few take the shape of pistols - just to remind us, as the artist says, that violence is lurking right here in our own backyard. And isn’t that just like a carnival? The strange and alluring juxtaposition of the morbid and the glitzy - with just a hint of danger.

If Cave does not produce the kind of visual experience once associated with art museums, it’s not so much that the artist has fallen short as that the mainstream contemporary artworld has not called for it. A dazzling, politically correct (though not especially responsible) carnival of grievance is quite sufficient, thank you.

.jpg)