“All my life I've been expected to acknowledge the power and beauty of pictures made by white artists that only have other white people in them; I think it's only reasonable to ask other people to do the same vis-a-vis paintings that only have black figures in them. […] My work is not an argument against anything; it is an argument for something else.”.. Kerry James Marshall

Race is an open wound in American society. Kerry James Marshall addresses it head on, and

more often than not, the paintings in this thirty-five year retrospective achieve what the artist calls “existential authority”. They command attention for how they look, not

just for the issues that they raise. His

abstract, cut-paper collages from the early eighties are dynamic and engaging.. Concurrently, he was beginning to develop a figurative

style. In one transformative piece from 1986, he painted both genres

side-by-side, declaring the personal goal of moving beyond conventional

abstract self-expression and defiantly asserting black identity with figurative art. Forecasting

the direction he would take, the face was highly stylized and leering. His subsequent success in large scale narrative

figures in pictorial space over the next decade is especially remarkable considering that his techniques

were self-taught. The old masters of

heroic European painting learned to compose with proportion, perspective, and

anatomy from living masters, but Marshall had to study the

past. He quotes a variety of historic painters, not all of them figurative, from Medieval icons to Cy

Twombly. The strong diagonals of his recent

38-foot mural may have come from Tintoretto. With a tireless work ethic, an endlessly inquisitive mind, and an enormous chip on his shoulder, in ten years he created a fascinating and unique style of monumental narrative figure painting.

His projects are the most successful when they put a

positive spin on the life and places he has personally known. The failed dream of inner-city housing

projects are an easy target for racial resentment – but Marshall paints them as

places where lives, like his, could grow and eventually prosper. “Many Mansions”

was the first Marshall painting that I ever saw, twenty-five years ago, back when major

museums, like the Art Institute, were beginning to acquire his work. It delivers a strong sense of time, place,

and hope for the future. It was the first contemporary ‘American Scene’ painting

that the museum had acquired in over fifty years. But anger and

resentment seethe throughout his entire career. He straddles the boundaries between ideal and

irony, sweetness and saccharine, homage and parody, strength and stiffness. Some of his most charming images depict

romantic couples. But when lovers remove their clothes, the artist draws and even labels them as

monsters: “Frankenstein” and “Bride of Frankenstein”. An articulate spokesman, the

artist has raised the concern that “white figures in pictures representative

of ideal beauty and humanity are ubiquitous.” But figuration has not been exclusively white in museum collections of 20th Century art, and what kind of

alternative has Marshall offered? Often his bodies feel as stiff as robots, conflating

the slave race from the past with the mechanical slaves of the future. It’s quite a contrast with the lyrical

figuration of earlier African American masters like Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, and Archibald

Motley. He rhetorically scourges the racist

race at least as often as celebrating his own ethnicity, depicting Blacks as he imagines Whites

see them. At the miserable extreme, he toys with memorializing the Caribbean servant who inexplicably

slaughtered Frank Lloyd Wright’s family at Taliesin.

His contemporary figures live in the commercial world of

Sunday newspaper supplements. Their

clothing is clean, starched, and colorful.

He may have designed it himself, but it appears mass produced, and impersonal. Other than those who resisted slavery,

he does not depict famous African

Americans. Other than artists or hair stylists, he does not represent people at

work. The faces he depicts do not express minds anywhere near as brilliant as his own, and he seems ever more ambivalent about the world of high culture which he has conquered. . But whatever the limitations of his subject matter and mission, he is the first artist to fill the entire top floor of the MCA with great figure painting. And he does not focus on degradation like many other contemporary African-American artists who have been promoted into the academic artworld (Kara Walker, Theaster Gates, Rashid Johnson)

Gallery signage mentions the artist's use of egg tempera, but ignores the elephant in the room. In this painting, and all that follow, Marshall quotes the American tradition of blackface minstrels. It's how white Americans, in the hey-day of Jim Crow, liked to think about African Americans.

The grin on this mask is somewhat sinister. He could be a prankster. He could be a serial killer. He could be an artist striking a disruptive but acceptable pose.

I wonder if the artist was doing janitorial work at that time to pay the bills? I'm guessing that Marshall came up the hard way, working odd jobs to support himself until a big east coast gallery discovered him. Without an MFA, he did not begin teaching until his gallery career had already been established.

I'd like to see a complete exhibit of his early abstract collages. They 're quite enjoyable.

Here's the abstract and figurative genres side-by-side. It's amazing how far he advanced beyond this in the next seven years.

This is a nice painting - but I'm not disappointed that he soon left behind all this hoodoo mumbo jumbo.

One of my early favorites, I've seen this painting many times. The Smart Museum was quite smart to acquire this when they did.

A wonderful piece with an unusual subject matter. It's hard to find heroic celebrations of a vigorous and healthy heterosexuality in contemporary painting these days.

A fine vision - regardless of its strange notions of the human genealogical tree.

When was the last time a contemporary American artist depicted Adam and Eve ?

One of the best American Scene paintings ever done -- and then he topped it twenty years later with "School of Beauty" that hangs on the opposite wall in this exhibit.

I am so glad he didn't pursue this kid-stuff direction any further.

How many paintings could go into a museum of contemporary art -- and also be reproduced in a boy scout handbook?

This is the painter's golden period, as far as I'm concerned.

The Art Institute bought this painting in 1995 and immediately put it up in a temporary display where casual museum visitors, like myself, might stumble upon it.

I was thrilled.

There is something so sad - and real - about this middle-class interior.

Another one of my favorites -- this room size cityscape feels exactly how Chicago's West Side feels to me on a too-sunny day.

KJM developed many abilities -- but drawing a moving figure has not been one of them.

This piece is a disaster.

Doesn't this belong on the wall of a Door County supper club? These parodies of popular art seem such a waste of his talent.

Unusual - and effectively dramatic.

An over-sized cartoon.

As my New City colleague has written:

But in consistently seeing the color black as presence rather than absence, Marshall neglects its power of negation: “the blackness of Blackness.” Seen in this light, Marshall succeeds best where his pictures are least agreeable, for example in the difficult (its forms barely discernible) “Black Painting” (2003-6). It shows a bedroom, a figure on a bed, and a copy of Angela Davis’ collection of prison writings “If They Come in the Morning: Voices of Resistance.” “The offense of the political prisoner,” Davis wrote, “is his political boldness, [and] his persistent challenging—legally or extra-legally—of fundamental social wrongs.” At his best, as here, Marshall is equally bold in challenging the social fact of racism.

There is certainly no denying the "power of negation" for a certain kind of intellect.

But there's not much to look at here.

This parody is not so attractive as a painting - but would work well as a cartoon in the New Yorker.

The artist has succeeded in escaping the run-down city, but not in escaping a picture post card mentality. Is this meant to be ironic?

Bride of Frankenstein, indeed.

That colorful chair seems like a homage to Gerhard Richter or a similar artist.

ouch. A rather negative view of masculinity.

Does this mass-murderer have a mischievous look? Was it any less mischievous of the artist to label this a portrait of a fictional actor?

A handsome painting, though it does suggest that the most distinctive quality of it's subject, Beryl Wright the art museum curator, was her blackness.

I can't follow the argument on the signage that accompanies these generic portraits of black artists.

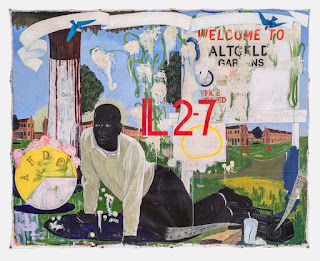

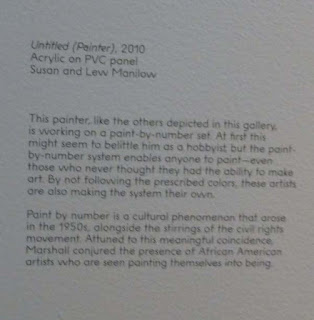

How can they "paint themselves into existence" by doing paint-by-numbers ?

If Marshall was intending to make his large abstract paintings annoying and unpleasant, I believe he succeeded.

************************************

Here are some other paintings which feature black faces:

The most lyrical come from Ajanta, dating back at least 1500 years. The women are all beautiful - but they may represent monsters in disguise -- waiting to devour those who cannot distinguish appearance from reality.

Andre Pierre

Here's a Haitian painting that offers a similar folkloric feeling

Hale Woodruff

Woodruff's 1930's murals from the Talladega College library traveled to Chicago a few years ago - and they offer a similar focus on African Americans-- though their skin is not universally black.

Here's Woodruff's depiction of a slave revolt on the Amistad. It's violent enough - but there is not a drop of blood -- and one might say it was done in a major rather than minor key. It reminds me of 16th C. Mughal battle scenes.

Archibald Motley

This piece offers an interesting contrast with Marshall's scene of a nude woman before a mirror:

I love this painting! It's another one of his great ones.

Kehinde Wiley

Here's a contemporary painter that also works with African American subjects and historical European styles.

But his commitment to marketing seems way above any concern for the aesthetics of painting.

( I reviewed his Chicago show

here )

William H. Johnson

By coincidence, the above painting is currently on display at the Art Institute in a special exhibit of American painting from the 1930. According to the signage, the artist was well trained, lived in Europe, and returned home to "paint his own people". This piece looks pretty good -- it's too bad most of his recognition has been posthumous.

Ed Clark

By the way, however rare black faces may be on the walls of American art museums - the work of African American abstract artists is even more rare.

I had never seen one until the Art Institute gave a brief and small exhibit to Ed Clark, which I discussed

here.

When Marshall decided not to continue as an abstract painter in the 1980's, he was making a good career move.

***********************

Peter Schjeldahl has reviewed a similar show at the Met Breuer. The same paintings were on display, but apparently the signage was different. And instead of offering a reading room of popular magazine depictions of black people, it offered a "show within a show", curated by Marshall himself, of selections of art from the Met. As Schjeldahl puts it:

The gesture confirms him as the chief aesthetic conservative in the company of such other contemporary black artists as David Hammons, Kara Walker, and Fred Wilson, who are given to conceptual and pointedly social-critical strategies. Marshall’s untroubled embrace of painting’s age-old narrative and decorative functions projects a degree of confidence that is backed both by his passion for the medium and by the authenticity of his lived experience.

And as yet another aesthetic conservative, I strongly agree!

But Schjeldahl did not experience the anger and ethnic conflict that I did. Instead he gives the show a more positive spin: "

An exhilarating retrospective at the Met Breuer is not an appeal for progress in race relations but a ratification of advances already made."

Though he did note, as I did, that the most prominent and one of the few depictions of white folk in the show is the bloody head of a slave master severed by Nat Turner..

My favorite work in the show is the Fragonardesque “Untitled (Vignette)” (2012), in which a loving couple lounges in parkland made piquant by a pink ground, a dangling car-tire swing, and an undulating musical staff in silver glitter, with hearts for notes. Marshall’s formal command lets him get away with any extreme of sweetness or direness, exercising a painterly voice that spans octaves, from soprano trills to guttural roars.

Yikes! This was Schjeldahl's favorite piece ? I am totally puzzled by his reaction.

I would like to share the optimism of his concluding sentence:

Marshall’s “Mastry” has a breakthrough feel: the suggestion of a new normal, in art and in the national consciousness. ♦

But that reaction applies to only one of the directions taken by the artist. Unlike Horace Pippin, Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, and Charles Wilbert White ( the African American artists whom he chose for the tribute section of this exhibition), Marshall is not content to visualize a social ideal. He also likes to participate in contemporary academic art discourse.

Apparently Schjeldahl does not care much for the other things that he does. And neither do I.

*************

Robert Colescott

Schjeldahl's review introduced me to this artist. Hope he gets a show in Chicago some day.

...and luckily he did - and I wrote about it here

Indeed, one of the most satisfying aspects of Marshall’s paintings on a technical level is the faces and bodies of his subjects, confidently worked out in a gorgeous, velvety matte black.

Using this formula for depicting black subjects, and by extension black subjectivity, Marshall has mined the implicit normalizing codes of Norman Rockwell-like single and group portraiture to great effect.