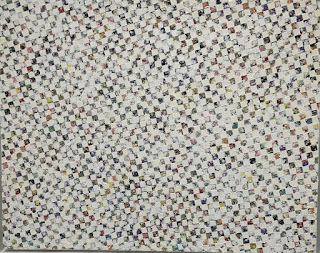

One, 126" x 180"

Detail

A review of Suchitra Mattai "Osmosis" at Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago

************

In tribute to her ancestors who left India in the 19th Century, Suchitra Mattai (b 1973) has laid out this exhibition so that the viewer moves through the galleries as if visiting a Hindu temple. In the final room, the garbhagriha (inner sanctum) she has installed a four foot replica of a temple made of salt - as if it had just emerged from the sea of memory - leaning dramatically to one side - as if it will soon sink back beneath the waves of forgetfulness.

It soon becomes apparent that the only deity being worshiped here is herself and the quality of the art need not represent any higher being - with two exceptions. Casts were made of Hindu temple sculpture to frame some of Mattai’s pieces. They remind us of just how effectively that tradition can conflate architecture with sacred narrative.

But the most remarkable exception is a wall size tapestry that Mattai made herself. Sourcing traditional saris from her own family as well as elsewhere, she has interwoven them into a magnificent, alluring design that has the exotic allure of the Ajanta cave paintings. The artist is probably familiar with other cycles of ancient painting, but the fifth century Ajanta frescoes are the ones best known in the West. Though superficially secular, they are treasures of world sacred art.

Titled “One”, Mattai’s piece shows us the backs of three women with golden halos. They appear to be leading us up from blue water as they ascend the peaks of a great mountain. Even if the artist intended them to only represent her own ocean crossing ancestors - I want to follow them too. Something about them is so passionate, glorious and mysterious. Hopefully the Textiles Department of the Art Institute will acquire this piece so I can see it again someday adjacent to other great fiber art.

Everything else in the show is also well made - especially the temple of salt. How the hell did she do that? But is this show really about "the flexibility of storytelling" as the artist proclaims? How much does it actually reveal about the artist and her family beyond that they identify as Hindus from India and that she identifies as female? All of the figurative pieces are female-centric - even the one that actually depicts a male or two. We may admire the artist for respecting her rich cultural legacy as well as gender - but is that controversial anywhere except in places like Afghanistan?

And is "flexibility" of storytelling" really worth looking at anyway ? Wouldn't you rather have a storytelling that is convincing or intriguing or uplifting or shocking ? Gauging flexibility is an academic literary project - as is celebrating an identity that is currently acceptable ( female person-of-color).

Suchitra Mattai is a compelling artist only when she steps away from academic trends and shows what she really wants us to know about herself: she is descended from three goddesses. And I am inclined to believe her.