"Preacher", 1952

This has been a summer of twentieth century American figurative art at the Art Institute of Chicago. John Singer Sargent presented the glamor of wealth, Ivan Albright shared the terror of mortality; but Charles White addressed something much more momentous: the ongoing struggle of America’s racially identified underclass. It’s the catastrophic national disgrace that’s embedded in our nation’s founding documents. After two hundred and fifty years of armed and political struggle, responses to the African-American experience still drive the campaigns and agendas of each and every national administration – as well as American popular music. White’s work has the prophetic gravitas required– especially his stark black and white linocuts. As pictorial space collapses, all energy is pulled into his figures – especially the powerful heads and hands. They are solid and earthbound like nothing else in American art.

Often, his work reached beyond the world of art collectors. The exhibit includes a study for his 1943 mural, “The contribution of the Negro to American Democracy” at Hampton University. It demands social recognition and respect, while it's angular, imploding planes have all the jagged intensity of Picasso’s analytical cubism. The exhibit also includes his 1956 drawing “Oh Freedom” that was reproduced for a 1960 NAACP rally in Los Angeles that featured both John F Kennedy and Martin Luther King. It depicts a sturdy young man scattering seeds with an open, confidant gesture. Other than Abraham Lincoln and John Brown, all of the people that White depicts are black -- and all of them are sturdy.

White’s art participated in the consecutive political movements of his lifetime: from Communism to Civil Rights to Black Power. Yet it feels too vulnerable and personal to be just propaganda or political cartoon. As quoted within gallery signage, he once declared “Paint is the only weapon I have to fight what I resent”.

Born just one year after Jacob Lawrence, White is far removed from the ebullient aesthetic of the Harlem renaissance. His work is about struggle, not celebration. Often it is grim and unpleasant to view. When reduced to one shape and one color – like his linocut portraits - the pieces can be quite powerful and enjoyable, with faces honed by suffering.. Otherwise, they often feel confused, distorted, and cluttered. Over the course of his forty year career, however, one might note how his faces become more natural and his designs more lyrical.

It’s quite a journey from “Soldier” (1944) to “Banner for Willy.”(1976). Both work with tragic themes: an African American soldier fighting to preserve an unjust society against an even worse opponent -- followed thirty years later by a eulogy for his murdered uncle. Brutal, angular distortions have been replaced by more natural figuration within an almost beatific design. The artist has moved from black is strong to black is beautiful - especially in the most recent piece in the exhibit, “Sound of Silence” (1978), done one year before his death. A serious, vigorous looking youth seems to be conjuring up his inner spirit that takes the form of a twisting, fulsome conch shell. Nothing is going to stop that young man from leading the kind of life that he wants.

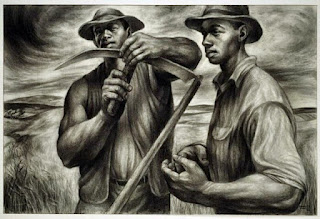

Much of the work in this show might best be called illustration as formal concerns take a back seat to emotional political narrative. One exception would be “Harvest Talk” (1953), the artist’s most explicit homage to the Soviet Social Realist art of that time. Not only do the characters feel as real as a documentary, but they flourish within rather than fight against the pictorial space that envelops them. It seems to sanctify both the men and the work that they are doing. Most postwar American art has been about the self expressive individual - defying social norms with heroic resistance, flagrant irony, or bitter alienation. This piece, however, celebrates humans in community with each other and the planet. It’s such a masterpiece. (though one might note that the Noble Farmer is a trope in Nazi as well as Soviet art)

"Harvest Talk", 1953

*****************

Lee Ann Norman's New City review also draws attention to "Harvest Talk", and adds some additional biographical information, including the following:

Most (Los Angeles) artists fell into one of two camps: those who valued traditional figuration to convey black pride and those who preferred newer techniques such as performance and abstraction, or assemblage to achieve those means. Eventually, White became influential enough to convince the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) to focus on L.A. artists and include contemporary work rather than solely existing to compete with New York’s Metropolitan Museum or Chicago’s Art Institute and their dedication to old European masters. Soon, LACMA became one of the only places black artists living on the West Coast could show their work outside of their own neighborhoods.

This seems to suggest that White convinced someone at LACMA to show "the newer techniques" of African American expression, as well as the kind of "traditional figuration" that he himself practiced. I wonder where one might find the source of such information.

***********

In the exhibition catalog, Kerry James Marshall also discusses the current retrospective while paying homage to his mentor:

"---- Simply emulating his work wasn’t enough for me; I tried to be Charles White in every way I could."

He singles out "Seed of Love" and "Black Pope (Sandwich Board Man" as " the most poignant creations of Charlie’s oeuvre. Put those alongside Francisco de Zurbarán’s Saint Serapion, and Saint Francis of Assisi according to Pope Nicholas V’s Vision"

He also notes that:

By the time I enrolled at Otis as a full-time student in January 1977, a revolution was under way. A catchall department called Intermedia—where conceptual art, video, performance, installation, and land art were routine—was advancing the newest wave of art theory. Those insurgents had just about completed their dismantling of traditional, humanist craft workers. The final stroke was the takedown of a medieval bronze statue in the campus quad of the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, dragged down by a rope tied to the bumper of a truck driven by the chairman of that department. When the dust settled, everything I was drawn to Otis and Charles White to learn seemed to crumble as well.

This might suggest that, as far as Kerry James Marshall is concerned, the "traditional humanist craft" as practiced by Charles White could not co-exist with the new techniques introduced into art schools in the 1970's. He further noted that of the four black students then studying with White, he, Kerry James Marshall, was the only one who would have an art career "built primarily on figuration"

And then there's this provocative paragraph:

It was always clear with Charlie that to make good work, one had to know a thing or two about more than how to draw or paint. He had a scholar’s interest in history, which informed the work he made. He often said your work should be about things that mattered but reminded us all to concentrate on making the best drawings we could, adding, “the ideas will take care of themselves.” Similarly, the art historian and theorist Rosalind Krauss, writing about the conceptual photographer Cindy Sherman, critiques the tendency of analysts to privilege meaning in an artist’s work over the mechanisms that structure our comprehension of it: “Sherman’s doll photos are a statement of what it means to refuse to an artist the work that he or she has done—which is always work on the signifier—and to rush headlong to the signified … the constructed meaning, which one then proceeds to consume as myth.”

At this point in time, such a statement might seem reactionary, conservative, and backward.

If, or when, the status of "the newer techniques" falls below that of traditional figuration -- such a statement may appear prophetic.

Among African-American artists who address African-American identity, the conceptual/installation/perfomance/assemblage types seem to be the majority among those who show in prominent local venues: William Pope L., Rashid Johnson, Theaster Gates, David Leggett, and Tony Lewis are names that come to mind -- I'm sure I could recall more if such work interested me enough to go see it.

On the figurative side, the sculptor Preston Jackson is the only Chicago artist, other than Marshall, whom I can recall. Nina Chanel Abney, Greg Breda, and Jennifer Packer have all shown recently in our area, but none live nearby.

*************

Deanna Isaacs in the Chicago Reader quotes the show's curator, Sara Kelly Oehler, that the artist:

was dedicated to correcting the record on the African-American experience.

She goes on to note:

His larger-than-life portrayals of African-Americans (both famous and anonymous) radiate substance, presence, and agency. They were deliberate correctives to the rampant misrepresentation of blacks in white-controlled mainstream history and art.

One interesting example might be White's posthumous portraits of Bessie Smith.

Here is a photo - presumably used by the singer and her promoters to promote her career. She looks sassy and playful -- not incongruent with a singer best known for "rough", provocative sex songs.

Here is Charles White's linocut portrait of the singer as a soulful, serious, suffering person who, if she sang anything, would be singing prayerful hymns.

Which portrait is an accurate portrayal? Which is a rampant misrepresentation ?

Like his friend, Harry Belafonte, White would probably have been concerned with the celebration of recreational sex, drugs, and violence promoted by African American performers in the decades after his death.

He might also have been concerned with the aestheticization of failure as embodied by Theaster Gates' sculpture in a recent show at Richard Gray

In both cases, it might be said that black artists are presenting negative portrayals of black people for white businessmen to sell.

***

Deanna Isaacs also shares an intriguing theory concerning the conch shell that appears in some of White's last paintings. According to his son, it's a reference to the Caribbean origins of their family.